Imagine watching your city under siege. Rockets arching overhead, the sky lit up like a hellish fireworks show. You don’t know if the people you love will survive the night. Then, just as the smoke clears and the sun begins to rise, you spot a massive flag still waving over the fort. That’s the scene Francis Scott Key saw in 1814. And somehow, in the middle of all that chaos, he wrote a poem that would later become America’s national anthem.

Prisoner With a Front-Row Seat

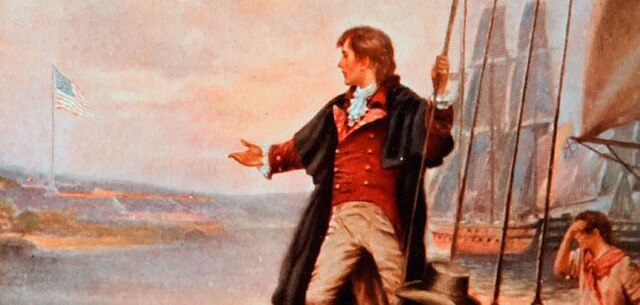

Key wasn’t a soldier. He was a lawyer. And kind of by accident, he found himself in the middle of the War of 1812, stuck on a British ship. He’d gone to negotiate the release of a prisoner and ended up being held until the British finished their bombardment of Fort McHenry.

From the deck of the ship, Key had a terrifyingly clear view of the attack. He saw the British navy rain explosives down on Baltimore through the night of September 13, 1814. Fort McHenry held the line. And in the morning, the American flag was still there. Key scribbled furiously on the back of a letter. The words just spilled out.

From Poem to Anthem

He titled it “Defence of Fort M’Henry” and published it shortly after the battle. Someone paired it with the melody of a British drinking song (because of course), and it spread quickly. People sang it in taverns and parades. The tune was catchy, if a little tricky to sing. And the words? Raw, proud, and full of awe.

It took more than a century for it to become the official anthem. Congress didn’t make it official until 1931. Until then, it was just one of several patriotic songs. But something about it stuck. Maybe because it wasn’t written from comfort or triumph. It came out of fear and hope and real danger. You can feel it in the opening line: “Oh, say can you see…”

More Than a Flag

We often forget how symbolic that flag was. The one Key saw measured 30 by 42 feet. It was sewn by Mary Pickersgill and her team in Baltimore. They made it big enough so the British could see it from a distance. Kind of a giant middle finger, if you think about it. “We’re still here. Still fighting. Still free.”

That flag now lives in the Smithsonian. And seeing it up close? It’s torn and worn, but still overwhelming. You realize that Key wasn’t writing about just a piece of cloth. He was writing about resilience. The idea that even after a nightmare of a night, something could endure.

Wait, There’s More Than One Verse?

Yes. Four, actually. But let’s be honest, almost nobody sings past the first. The rest get pretty heavy-handed with the 19th-century religious and patriotic imagery. There’s even a line that stirred controversy, about “the hireling and slave,” which historians debate over to this day. Key himself was a slave owner, which adds another complicated layer.

So yeah, the anthem is not without baggage. But that’s part of the deal with national symbols. They’re not perfect. They carry scars. They evolve, or at least they should make us think.

Singing Through the Noise

Over the years, the anthem became a litmus test. People stood with hands over hearts. Athletes kneeled in protest. The song has been at the center of debates about patriotism, race, and freedom.

But maybe that’s the point. Maybe the power of the Star-Spangled Banner isn’t just in the story it tells, but in the conversations it starts. It’s messy and emotional. Kind of like the country itself.

So next time you hear it, try listening like Francis Scott Key might have. With bombs in the air, fear in your chest, and a desperate hope that the flag would still be there.

Source:

1. Smithsonian Magazine – The Star-Spangled Banner

2. NPR.org – The Story of the Star-Spangled Banner

3. Britannica – The Star-Spangled Banner