The Roman Who Predicted Germs 2,000 Years Ago

You’re in a toga, swatting flies with a palm fan, and someone named Marcus Terentius Varro leans over his scroll and casually suggests that disease might be caused by invisible creatures floating in the air.

Wait. What?

Before microscopes. Before Louis Pasteur. Before soap was even widely trusted. This Roman scholar predicted the existence of microorganisms. Actual microscopic agents of disease. And then the world kind of… ignored him for the next 1,900 years.

This is the wild, slightly dusty story of how a man born in the age of gladiators basically whispered germ theory into the void and why we’re only just now appreciating how weirdly ahead of his time he was.

Marcus Varro wasn’t wrong. He was ahead of his time by centuries.

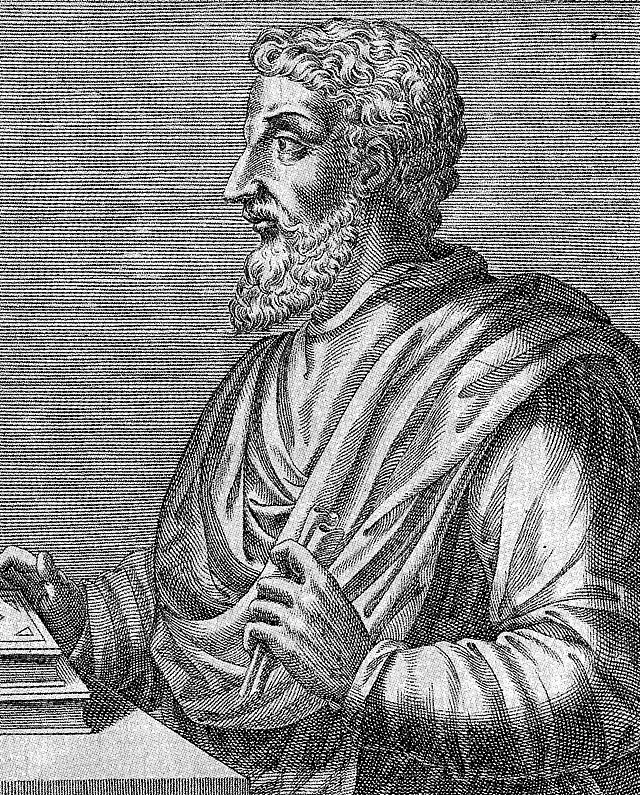

Meet Marcus: Rome’s Most Underrated Genius

Marcus Terentius Varro wasn’t a doctor. He was a polymath. That’s Latin for “I know a little bit about everything and probably a lot more than you.” Born in 116 BCE, Varro wrote over 600 books (only a few survive), covering everything from language to farming to military tactics.

Think of him as a one-man Wikipedia. If Wikipedia also ran farms and fought in wars.

But his real “wait, what?” moment comes in a farming manual, the De Re Rustica, written around 36 BCE. It’s not even a medical text. It’s a guide for landowners on how to run a proper Roman estate.

And in the middle of this very sensible, soil-focused text, Varro drops a sentence that should’ve caused the world to double-take for centuries.

The Sentence That Should’ve Changed Everything

Here’s what Varro wrote, more or less:

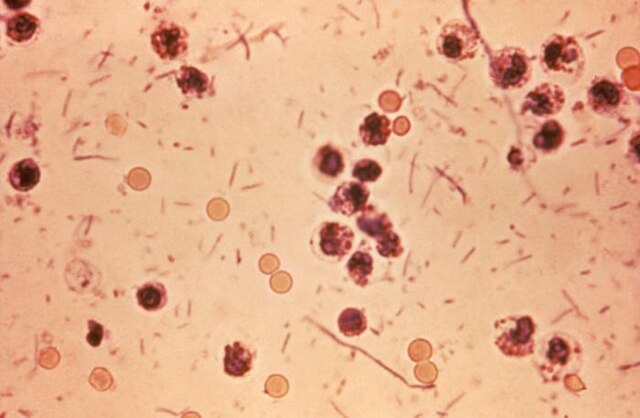

“There are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose, and there cause serious diseases.”

That’s it. That’s germ theory in a toga.

Tiny, invisible creatures. Floating in the air. Entering your body. Making you sick.

He wasn’t guessing about “bad air” or curses or miasmas. He literally describes microscopic organisms before the microscope even existed.

It’s like predicting TikTok during the invention of the printing press.

So… How Did He Know?

Here’s where things get interesting.

Varro didn’t know, obviously. But he observed. He noticed patterns. He saw that people living near swamps or stagnant water got sick more often. He made a leap, a really good one.

It wasn’t magic or divine punishment. Maybe, just maybe, something real was happening. Something small. Something invisible.

It’s the kind of intuitive science that modern thinkers dream about. A mental leap from observation to hypothesis without any of the tools we’d normally consider essential. No lab coat. No petri dish. Just a curious Roman with a sharp mind and a deep mistrust of wetlands.

The World Wasn’t Ready for Varro

You’d think this idea would’ve caught fire. That someone, somewhere, would’ve picked it up and said, “Hey, maybe we should look into this.”

Nope.

Instead, the world doubled down on miasma theory, the idea that “bad air” caused disease, like some evil fog rolling through town. That stuck for, oh, 1,800 more years.

Why? Because germs were invisible. And people like their threats visible. Angry gods? Easy to conceptualize. Demons? Spooky but familiar. But tiny bugs you can’t see living in your mouth? Too weird. Too unsettling.

It wasn’t until the 17th century, when the microscope was invented, that people even saw microorganisms. And it took another couple hundred years before doctors started washing their hands regularly.

Varro was right. We were just really, really late to the party.

A Guy Ahead of His Time (and Maybe Ours)

In a way, Varro feels kind of familiar. You know that one friend who says something slightly bonkers at dinner, like “aliens are real” or “AI will eventually write poetry better than humans” and ten years later, they’re suddenly a prophet?

That’s Varro. Except swap the dinner party for a Roman villa and the aliens for bacteria.

He’s a reminder that sometimes, the smartest people aren’t the loudest. And that really good ideas don’t always win, at least not right away.

Final Thoughts: The Wisdom Buried in Footnotes

It’s kind of poetic that Varro’s germ theory shows up not in a scientific manifesto, but in a casual aside in a farming guide. Like he was just tossing off brilliance between crop rotations.

But that’s what makes it stick with you. Because if someone could see that clearly, that early, what else have we overlooked?

Varro may not have gotten his moment back then. But maybe now, 2,000 years later, we can finally say: Marcus, you called it.

And we owe you one.

Sources:

1. Harvard University’s Loeb Classical Library – De Re Rustica

2. The Atlantic – The Roman Who Predicted Germ Theory

3. National Institutes of Health – Early Theories of Disease Causation