It was just another humid June morning on Mackinac Island in 1822 until a musket went off and tore open a man’s stomach. Literally.

The victim? A 20-year-old French-Canadian fur trapper named Alexis St. Martin. The shooter? A fellow trapper, probably not paying attention. The injury? A catastrophic, gory hole in St. Martin’s side that exposed his stomach. As in, people could see into his body. And yet, he lived!

That should’ve been the end of his story. Instead, it was the start of one of the weirdest and most important chapters in medical history. Because St. Martin didn’t just survive. He became a human science experiment. For ten years.

The Shot Heard Around the Island

Let’s set the scene:

Mackinac Island, June 6, 1822. A trading post operated by the American Fur Company. Alexis St. Martin, young and strong, works nearby. Someone’s cleaning or loading a musket, it’s not entirely clear. But the musket discharges at close range, the blast shredding through St. Martin’s ribs, tearing muscle, and blowing open his side.

He falls. Bleeding out. Internal organs exposed.

Dr. William Beaumont, a U.S. Army surgeon stationed at the fort, is called in. He examines the wound and pronounces what any reasonable doctor would: this guy isn’t going to make it.

But St. Martin didn’t follow the script.

A Hole You Can See Into

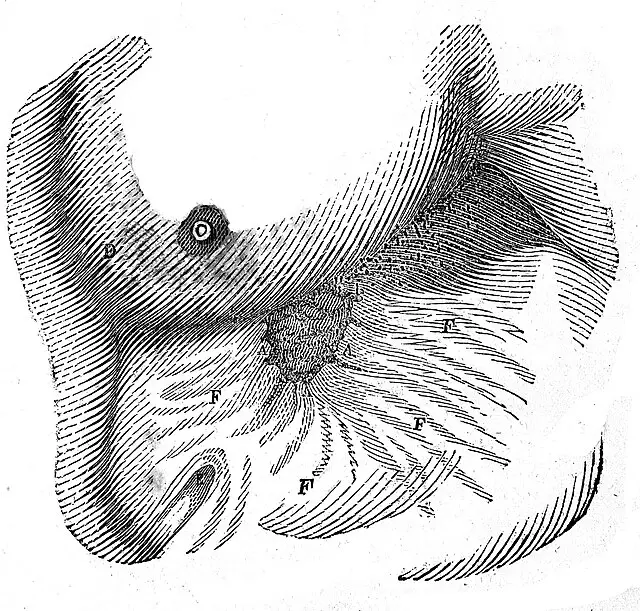

Against all odds, Alexis St. Martin survives. The wound heals, but not the way wounds are supposed to. His ribs knit. His tissue scars. But there’s this… opening. A gastric fistula. Basically, a permanent hole straight into his stomach.

Through this hole, you could literally watch food digest.

And that’s where Beaumont’s scientific brain kicks in. He sees not just a patient, but an opportunity. Because here’s the thing: in 1822, doctors didn’t know much about digestion. They had guesses. Theories. Some thought the stomach “cooked” food like a furnace. Others thought it just squished it until it became goo.

But now, Beaumont had something no one else in the world had.

A living window into the human body.

Alexis, the Reluctant Lab Rat

Let’s be clear, this wasn’t a mutual agreement between curious doctor and eager volunteer. St. Martin was poor, in pain, and barely educated. Beaumont hired him as a servant, but part of the job was letting the doctor dangle food on strings into his stomach, extract it, and analyze the results.

Sometimes Alexis agreed. Sometimes he didn’t. Sometimes he just ran away.

But every time he came back broke, sick, or homesick, Beaumont resumed the experiments. He tied meat to silk threads, inserted thermometers, even extracted gastric juices to see if digestion could happen outside the body.

Spoiler: it could. He discovered that gastric acid breaks down food chemically, not just mechanically.

This was revolutionary. It rewrote the textbooks. It laid the groundwork for modern gastroenterology.

But let’s not ignore the weirdness. This was a man, not a lab beaker. And he didn’t always want to be part of the show.

Science vs. Consent

Today, we’d call a lot of this unethical. Beaumont, brilliant as he was, treated St. Martin more like a tool than a person. He once asked the U.S. government to re-enlist Alexis in the army just so he could keep experimenting on him. He even referred to him as “my case” or “the man with the fistula,” not by name.

At the same time, you can’t entirely demonize Beaumont either. He kept Alexis alive. He documented everything. And he helped the world understand something nobody had before.

It’s messy. Which, let’s be honest, is usually how progress happens.

So, What Did We Learn?

In 1833, Beaumont published his work in a book titled “Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice and the Physiology of Digestion.”

Catchy, right?

But the content was gold. He proved:

1. Digestion is chemical, not just physical.

2. The stomach secretes acid continuously.

3. Emotions affect digestion.

4. Food breaks down at different rates based on its composition.

He also noted that stress slowed digestion, a fact doctors still repeat today.

This wasn’t just academic. His work led to better treatments for ulcers, dietary advice, and even early versions of antacids. And all of it came from one wounded fur trapper who just happened to get shot in the stomach.

Life After the Lab

Eventually, St. Martin had enough. He returned to Canada, married, and fathered six children. The hole in his stomach never closed. He wore a bandage over it every day. Sometimes, the bandage leaked.

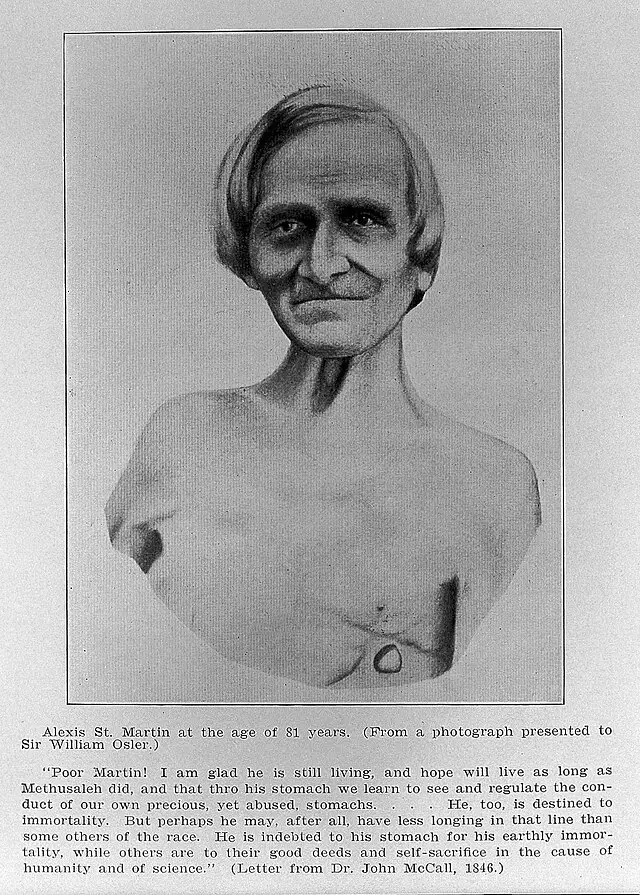

He lived to be 78 years old, which is honestly amazing.

And even in death, he couldn’t escape the science. After he passed, his family delayed the burial for days to make sure no doctor came to steal his body.

That’s how famous his stomach had become.

Why This Story Still Hits Hard

This story is about suffering. And science. And how medical breakthroughs often come from unexpected places.

It’s also about ethics. About where we draw the line. About whether the pursuit of knowledge justifies treating people like objects.

And honestly? It’s about survival. Alexis St. Martin should’ve died in 1822. Instead, he became a footnote in textbooks, a weird trivia question, a pioneer.

Even if he never asked to be.

Final Thoughts: The Hole That Changed Medicine

Here’s what sticks with me: Alexis didn’t volunteer for greatness. He wasn’t chasing glory. He just lived, and let someone study his insides because he had no better options.

And yet, his body gave science a lens it never had before. It helped doctors everywhere. It helped patients. It helped us.

Not bad for a guy who just wanted to trap furs and mind his own business.

So yeah, maybe next time you hear someone talk about the stomach, or you pop an antacid, or you eat something and wonder what’s happening down there, spare a thought for the man with a hole in his belly.

He helped us see inside ourselves.

Sources:

1. PBS: Beaumont and St. Martin

2. National Library of Medicine https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2769965/

3. Smithsonian Magazine