It sounds like the opening line of a tall tale: a man sets off from Japan in a small boat and ends up on the coast of America. But it’s not fiction. In 1815, a Japanese sailor named Otokichi was tossed into history by a storm he never saw coming.

Caught in the Wind

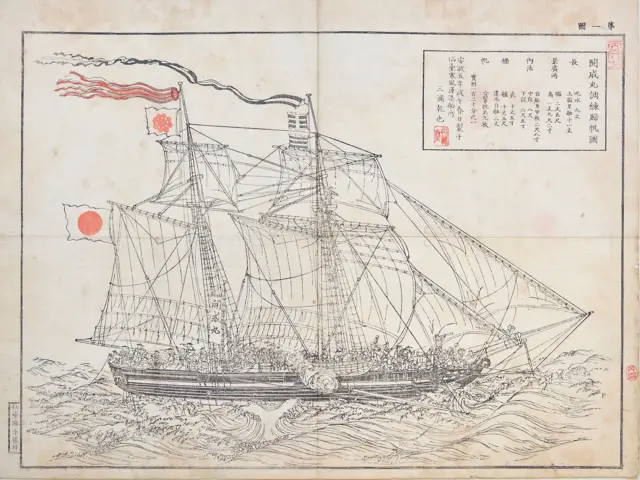

Otokichi was just 14 when he boarded the cargo ship Hojunmaru, a vessel meant to sail from Nagoya to Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Nothing too epic. It was a routine coastal trade voyage. Think of it as the 19th-century equivalent of a delivery truck run. Only the sea had other ideas.

A sudden storm blew the ship far off course. Like, really far. The rudder broke. The sails were shredded. And then the current took over. The crew was at the mercy of the Pacific. No GPS, no radio, no hope of rescue. Just drifting, drifting, drifting.

There were 14 crew members when they left. After 14 months at sea, only three were alive: Otokichi and two others. They survived on rainwater, whatever fish they could catch, and probably a lot of grim luck. Eventually, in 1834, their boat washed ashore on the Olympic Peninsula in what is now Washington State.

Stranger in a Strange Land

Imagine waking up one morning and realizing the people around you speak a language you’ve never heard, wear clothes you’ve never seen, and look at you like you’re from another planet. Because, in a way, you are.

The Makah tribe discovered the castaways and treated them well. The news spread, and soon the three Japanese men were brought to Fort Vancouver, the Hudson’s Bay Company outpost in the Pacific Northwest. They were a novelty, sure, but also a problem. What do you do with three non-English-speaking sailors from a country that had closed itself off from the world?

Back then, Japan was deep in the Tokugawa Shogunate’s isolationist policy known as sakoku. Foreigners weren’t allowed in. Japanese citizens weren’t allowed out. Returning to Japan? Absolutely forbidden. Otokichi and his friends were, in the eyes of their own country, already ghosts.

A Pawn on the Global Chessboard

The British saw an opportunity. Maybe these castaways could help crack open Japan for trade. They sent Otokichi to London, of all places, to learn English and represent a human key to a closed kingdom. He was paraded around like a curiosity. Newspapers reported on him. People tried to guess his age, his background, his thoughts.

Eventually, Otokichi was recruited for a diplomatic mission to return to Japan, this time under the British flag. But it didn’t work. Japan refused them at the border. The mission failed. Otokichi wasn’t even allowed to step foot on his homeland.

He must have felt like a man without a country. Too Japanese to belong in the West. Too foreign to be accepted back home.

Reinvention and Resilience

But Otokichi didn’t vanish into obscurity. He adapted. He lived in Macau, then Singapore. He took the name John Matthew Ottoson. He married, had children, worked as a translator, and became a bridge between cultures.

And in a quiet, poetic twist, he eventually returned to Japan. Not in body, but in spirit. When he died in 1867, his daughter sent a portion of his ashes to be buried near his birthplace. It was symbolic. A way of saying, you made it home.

Why His Story Still Feels Personal

Otokichi’s story is more than just a historical oddity. It taps into something deeply human. The way we adapt when everything familiar is ripped away. The longing for home. The resilience it takes to survive when you’re unmoored.

He wasn’t a hero in the traditional sense. He didn’t lead armies or write manifestos. He just kept going. Learned new languages. Made a life. Refused to disappear. In a world that keeps shifting, that kind of quiet determination is a superpower.

A Footnote with Heart

History books barely mention Otokichi. He’s a side character in stories about empires, trade, and colonization. But maybe that’s exactly why his story matters. Because in between the big events are the people who lived through them. Who drifted into history not by choice, but by chance.

And when you think about it, aren’t we all just trying to navigate our own oceans, one unpredictable current at a time?

Sources:

1. Smithsonian Magazine – Otokichi, the Jaoanese Castaway

2. WIkipedie – Otokichi