On August 29, 1911, a starving man stepped out of the wilderness and walked into Oroville, California. His hair was singed short, a traditional sign of mourning among his people. He was wrapped in rags and looked like a ghost. People panicked. They thought they were seeing a phantom from the past. And in a way, they were.

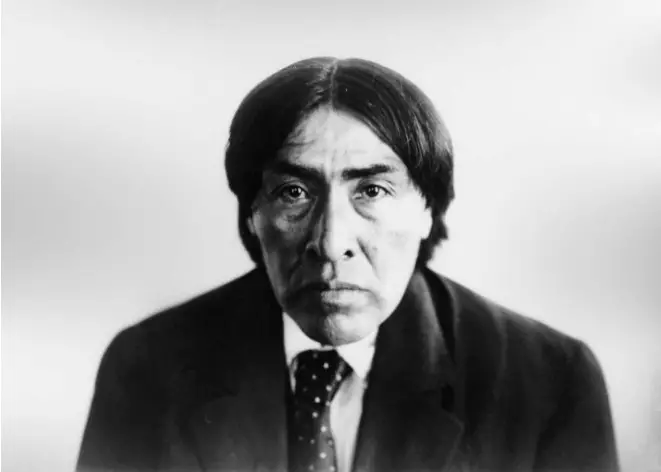

That man was Ishi. And he was the last known member of the Yahi people.

A Vanishing World

For years, the Yahi had been hiding in the rugged hills of Northern California, evading settler encroachment, the Gold Rush, and the genocidal violence that decimated so many indigenous groups in the West. Ishi was not the first to escape; in fact, his family had been killed by settlers years before. The survivors lived in isolation, hiding from the outside world, and largely from history itself. Ishi’s appearance on the outskirts of the town of Oroville in 1911 was a moment of desperation for him, yet also an unimaginable act of courage.

The Death of a Tribe

Imagine this: you’re the only person left who speaks your language. The only one who remembers the old songs, the names of rivers, how to hunt in silence, how to make fire with sticks and stone. Everyone you ever knew is gone. Killed. Starved. Scattered. You’re the last thread in a tapestry being pulled apart.

That was Ishi’s world.

The Yahi were part of the Yana people, a group of Indigenous Californians who lived in the foothills and canyons of the Sierra Nevada. Before the Gold Rush, there were thousands of them. But then came 1849. And with it, came miners, settlers, disease, guns, and a government that paid money for Native scalps. Yes. Paid. Money. For scalps.

By the late 1800s, the Yahi were presumed extinct. But they weren’t.

The Hidden Years

For over 40 years, Ishi and a tiny group of surviving relatives lived in hiding. They built shelter in remote canyons. They only moved at night. They left no trace. They watched the world from the shadows, knowing it would destroy them if it saw them.

Then one day, Ishi was alone. The others had died. Illness, starvation, grief. He burned their bodies in the old way. Then, desperate, he walked into town.

The Man Who Shouldn’t Have Existed

The people of Oroville didn’t know what to do with him. He didn’t speak English. He didn’t even speak Spanish. He had no money, no papers, no past the white world could understand. Authorities put him in jail.

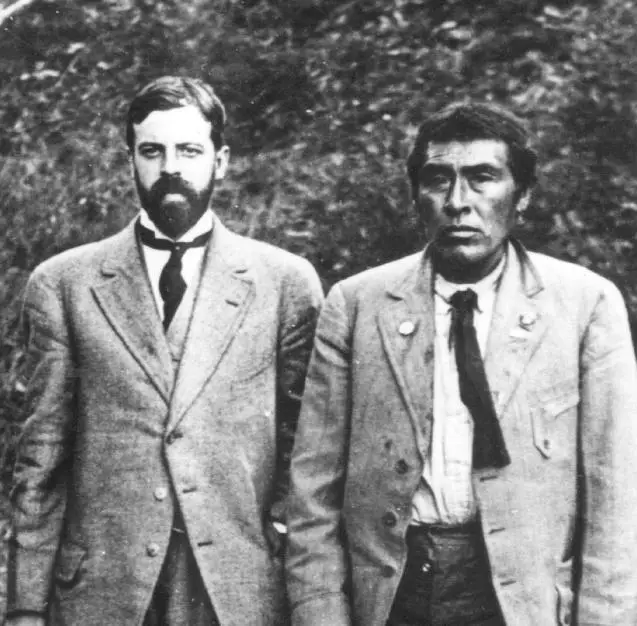

But news traveled fast. Anthropologists from the University of California came to meet him. One of them, Alfred Kroeber, realized the enormity of what had just happened: this man was a living link to a world thought lost. He called him “Ishi,” which just means “man” in Yana. (Ishi never revealed his real name, as speaking your own name aloud was taboo in Yahi culture.)

A Living Museum Exhibit

Kroeber brought Ishi to San Francisco. He lived at the university’s museum, where he worked as a janitor and, heartbreakingly, as a living exhibit. Crowds came to watch him demonstrate how to make arrowheads, how to start a fire, how to shape obsidian tools. He wasn’t bitter. At least, not outwardly. He was patient. Quiet. Kind. He liked smoked cigarettes and roast beef. He made friends. He loved children.

And yet, he was always alone.

Imagine being admired for your skill in making tools your people once needed to survive, while knowing your people are gone.

Ishi’s Final Days

In 1916, just five years after he emerged from the wilderness, Ishi died of tuberculosis. The disease had ravaged Native communities for decades. He didn’t stand a chance.

Despite Kroeber’s wishes, Ishi’s brain was removed during autopsy and sent to the Smithsonian. This, after a life defined by dignity, silence, survival.

It wasn’t until 2000 that his remains were finally returned to descendants of the Yana people and laid to rest.

The Last Voice

Ishi’s life was a tragedy. But it was also a testimony.

Through him, we caught a fleeting glimpse of a world wiped out in silence. He showed us what was lost. And what could still be remembered. He spoke Yahi for the last time, and researchers recorded it. He taught the old ways to anyone willing to listen. He didn’t want to be famous. He just wanted to live, and he did so with grace.

His story isn’t about the past. Not really. It’s about how the past haunts the present. It’s about how survival can look quiet, even invisible. It’s about how being the last doesn’t mean being forgotten.

Sources:

1. Heizer, Robert F., and Theodora Kroeber. Ishi in Two Worlds. University of California Press.

2. Smithsonian Institution Archives

3. Native American History of Northern California