He never sang on stage. But without him, karaoke night and every musical you’ve ever seen might not exist.

Picture this. You’re eight years old. You’re in music class, standing next to a kid who smells like glue, singing “Do, a deer, a female deer.” And you have no idea that you’re part of a thousand-year-old musical conspiracy cooked up by a monk in Italy who just really wanted his choir to sing in tune.

Enter: Guido of Arezzo. Possibly the most influential music teacher you’ve never heard of.

The Chaos of Pre-Guido Music

Let’s go back about a thousand years, to the early 1000s. Music was a mess. Imagine trying to bake a cake without a recipe, just someone describing it to you from memory every time. That’s how chants were taught. If Brother Aidan sang it slightly differently from Brother Benedict, tough luck. You learned whatever version you heard, and that became your version.

Music was passed down orally. No sheet music. No scale. Just vibes.

Guido thought this was… inefficient. And honestly, kind of a disaster. So he set out to change it.

A Monk with a Pen and a Plan

Guido was a Benedictine monk in Arezzo, Italy. He was smart, a little obsessive, and kind of a nerd for order. He believed music could be learned logically. That instead of brute memorization, singers could be taught using written cues. It was a radical thought at the time.

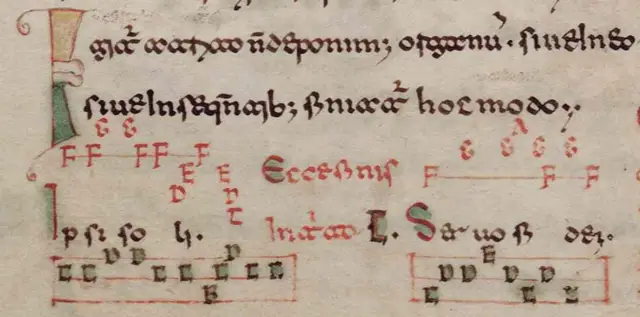

His big breakthrough was the invention of the staff notation. Before Guido, there were some attempts at squiggles and neumes above text to suggest pitch, but it was more like guessing. Guido introduced a four-line system where each line had a specific pitch.

This meant, for the first time, singers could read music.

He also created the “Guidonian hand,” a visual tool where notes corresponded to parts of the hand. Kind of like if you turned your palm into a cheat sheet. It sounds weird but was honestly genius, especially in a world where paper was expensive and most people were illiterate.

The Birth of Do-Re-Mi

But Guido’s flashiest legacy? The thing you probably still hum on your walk home?

The solfège syllables: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti.

Only back then, they were slightly different. Guido used a hymn to Saint John the Baptist, where each line of the verse started on a new note. He took the starting syllables: Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, and La. Later, “Ut” became “Do” for easier singing, and “Si” (later Ti) was added to complete the scale.

Think about that. A medieval monk rebranded a prayer and accidentally created the foundation for Western music education.

Not Everyone Was a Fan

Of course, not everyone was into it. Some monks thought Guido’s innovations were shortcuts. Like, “Back in my day, we memorized chants for ten years and liked it.” Others feared that writing music down would weaken memory.

But Guido had results. He could teach a choir in a fraction of the time. His students actually sang in tune. His methods spread faster than a chant at Easter Mass.

He got invited to Rome to show off his system. That’s like being called to perform at the Vatican’s version of America’s Got Talent.

The Long Echo of a Simple Idea

What’s wild is how far Guido’s ideas traveled. His staff eventually became the five-line system we still use. His solfège syllables are taught in music classes from Tokyo to Toronto. Pop singers, opera divas, jazz nerds, and third graders all owe something to him.

And yeah, The Sound of Music popularized it for a whole new generation. But Julie Andrews was just echoing a very old tune.

Why It Still Hits Different

Guido of Arezzo reminds us that sometimes the biggest revolutions come from someone just trying to make life easier for their friends. He didn’t set out to become a music legend. He just wanted people to hit the right note.

There’s something poetic about that. The quiet monk. The humming choirs. The long thread of sound stretching across centuries.

So the next time you hum a scale or read a bit of sheet music or clap off-beat at a concert, maybe tip your imaginary hat to Guido. Without him, music class would still be a game of telephone.

And honestly? That would’ve been a disaster.

The Takeaway: One Voice Can Change the World

What Guido teaches us isn’t just about music. It’s about what happens when you see a flaw in the system and dare to fix it. He wasn’t a famous composer. He didn’t lead armies. He didn’t seek fame.

But his simple, brilliant idea—the desire to make learning easier, clearer, better—reshaped history.

In a time when ideas were limited by memory, Guido gave the world a way to write the invisible.

So the next time you hum a tune, follow sheet music, or teach a child to sing do-re-mi, remember the monk who made it all possible. Remember the candlelit rooms of Arezzo. The ink on parchment. The notes that refused to fade.

Sources:

1. Hoppin, Richard. Medieval Music (Norton, 1978)

2. Crocker, Richard. A History of Musical Style (McGraw-Hill, 1966)

3. “Guido of Arezzo” – Britannica

4. Dolmetsch Music Theory Online

5. New York Times: “The Medieval Monk Who Taught the World to Sing” (2021)