He was a soldier, a prisoner, a runaway, and eventually… a Cherokee. Not by blood, but by bond.

Ludovic Grant’s life sounds like something out of a historical novel, but almost no one remembers his name. That’s wild, considering he helped shape the relationship between Scotland, Britain, and the Cherokee in the 18th century, and left a legacy that rippled through generations, including one that would lead to a U.S. president.

From Highland Battles to Colonial Backwoods

Grant was born in Scotland, sometime around 1690. He fought in the Jacobite uprising of 1715, supporting the Stuart cause. Spoiler: the Stuarts lost. Grant was captured at Preston, marched south in chains, and imprisoned.

Here’s where the story turns. Instead of rotting in jail, Grant was transported to the American colonies as punishment. Think of it as 18th-century exile. From rebel to indentured servant, he landed in Charles Town (now Charleston, South Carolina), probably bitter and still nursing old loyalties.

But something changed.

A Trader Among the Cherokee

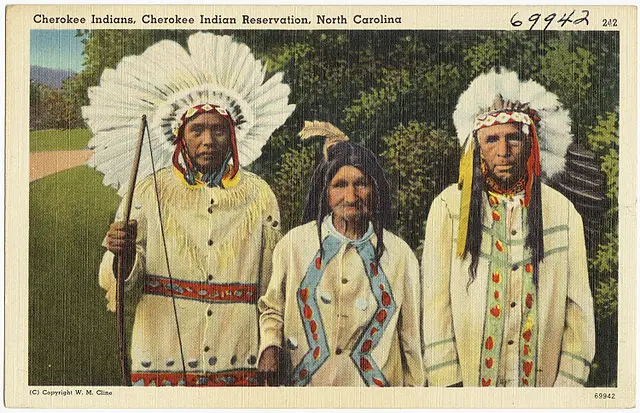

By the 1720s, Ludovic Grant had re-emerged as a trader in Cherokee territory. That alone is a pivot. It meant leaving behind the coastal British world and entering the rugged, sovereign domain of the Cherokee Nation, highlands of a different kind.

And he wasn’t just trading beads and knives for pelts. Grant learned the language. Married into the tribe. Raised a family. The Cherokee didn’t just tolerate him. They accepted him.

He wasn’t an observer. He became part of the story.

Writing from the Edge

What we know about early 18th-century Cherokee life comes in part from Ludovic Grant’s own words. In 1730, he wrote a long letter to James Glen, the Royal Governor of South Carolina. It’s not a dry merchant’s report. It’s vivid, personal, and layered with warnings about how British meddling might backfire.

He wasn’t romanticizing the Cherokee. He was just being honest.

His letter gives us an inside look at tribal politics, rivalries, and culture at a time when outsiders rarely understood (or cared to understand) what they were seeing. Grant described everything from diplomatic rituals to trade disputes. It’s one of the earliest written European accounts that treated the Cherokee as complex people, not just obstacles or allies.

A Legacy Carved Into Cherokee History

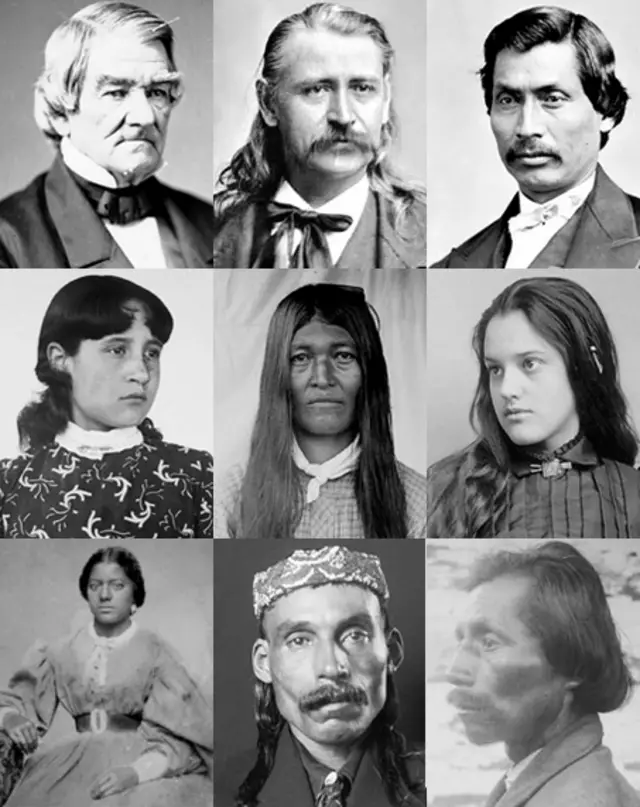

Today, the legacy of Ludovic Grant lives on not only through the stories of his descendants but also through the continued prominence of his bloodline within Cherokee leadership. Many Cherokee chiefs trace their ancestry back to Ludovic Grant, whose decision to marry into the Cherokee Nation centuries ago set in motion a lineage of leaders and advocates for the Cherokee people.

The blend of Scottish and Cherokee heritage found in Grant’s descendants is a testament to the complexities of identity, survival, and resilience. John Ross, among others, faced the daunting task of navigating the political pressures of both the United States government and his own people. His leadership was a reflection of the unique position in which he—and many of his peers—stood: straddling two worlds, yet firmly rooted in the heart of Cherokee culture.

Caught Between Worlds

Grant walked a tightrope. He saw the creeping danger of colonial expansion, but he also understood the fragile alliances that held peace together. He knew British ambitions wouldn’t stop at trade.

But he stayed.

Through the 1740s, Grant continued living among the Cherokee. His mixed-heritage children were raised in both cultures. He built bridges, not perfectly, not without flaws, but with sincerity.

His descendants would carry both Scottish and Cherokee blood. And one of them, many years later, would be John Ross.

The Grandson Who Became a President (Kind Of)

John Ross, born in 1790, was Ludovic Grant’s grandson. He would go on to become the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation during its most painful and defining era, the Trail of Tears.

Ross fought the removal policies of the U.S. government with everything he had. He led his people in court, in Congress, and finally, into exile. And while John Ross looked more European than Indigenous, his heart, his language, his home, were Cherokee.

Would John Ross have existed without Ludovic Grant? Probably not. It’s a strange twist of history. A Scottish rebel exiled to America becomes a Cherokee patriarch. His grandson becomes one of the most powerful Native leaders of the 19th century.

What Do We Do With Stories Like This?

It’s tempting to make Grant a hero. Or a symbol. But he was just a man. Complicated, inconvenient, in-between. He lived in the margins and tried to make something good out of it.

That might be the most honest legacy of all.

History isn’t always about empires or battles. Sometimes, it’s about the quiet, stubborn lives of people who didn’t fit neatly into either side. People who crossed lines, married across cultures, and tried to listen more than they spoke.

Ludovic Grant didn’t conquer anything. He didn’t write laws or raise armies. But he listened. He learned. And he stayed. And in doing that, he helped shape a story much bigger than himself.

Sources:

1. Grant, Ludovic. Letter to Governor James Glen (1730). South Carolina Archives.

2. Perdue, Theda, and Green, Michael D. The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. Penguin Books.

3. McLoughlin, William G. Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton University Press.