When Masabumi Hosono boarded the Titanic in 1912, he probably didn’t expect to become the most hated man in Japan.

He was just trying to get home. A low-profile bureaucrat with a quiet face and wire-rimmed glasses, Hosono had been on a government trip to Russia and was returning to Tokyo via Europe and America. He bought a second-class ticket on a grand ship making its maiden voyage. The RMS Titanic, hailed as unsinkable. And then, of course, it sank.

A Panic in the Night

It was cold and dark on the night of April 14. Iceberg cold. The kind of cold that makes your ears ring and your fingers stiffen. Around midnight, the Titanic scraped a jagged mountain of ice floating in the North Atlantic. The ship began to tilt. Panic spread like fire.

Hosono was woken by a steward and told to get up immediately. He rushed up to the deck, suitcase in hand. But by the time he reached the lifeboats, the crew had started enforcing the “women and children first” rule. Hosono stepped back. He watched as lifeboats lowered into the sea, leaving hundreds, maybe thousands, behind.

One Spot Left

At some point, one of the officers called out. There was room in a lifeboat. Two seats left, maybe just one. Hosono hesitated. This was the moment. The one we all imagine in our darkest what-if daydreams. Do you jump in and save yourself? Or do you stay behind and become a noble ghost?

He chose to live. He took the seat.

Hosono survived the Titanic disaster. He clung to that lifeboat in the freezing water until the Carpathia rescued him hours later. He made it to New York, then continued his journey to Japan. But if he expected relief or joy, he was sorely mistaken.

Betrayed by Survival

Back in Japan, survival was not seen as heroic. The country at the time valued stoic honor, even death over disgrace. Think of the bushido code. Think of samurai. There was an expectation, especially for men, to die with dignity rather than escape with shame.

Hosono’s story leaked to the newspapers. One even called him a “coward” who had brought dishonor to Japan. He was publicly shamed, mocked in cartoons, and even lost his job at the Ministry of Transport. The irony? His crime wasn’t murder, theft, or fraud. He had simply survived.

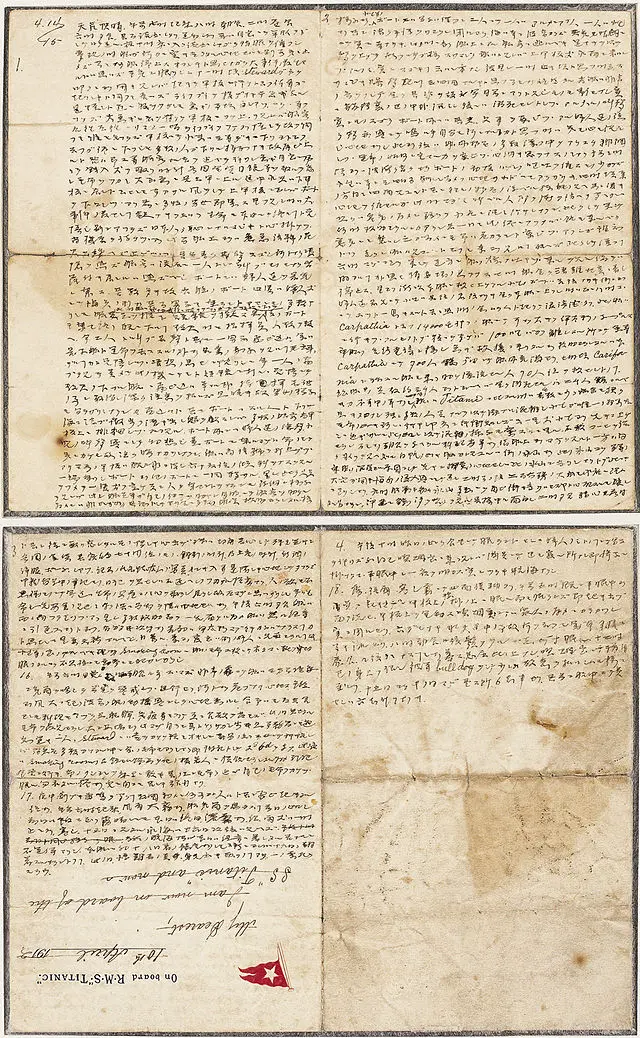

His Own Words

Hosono later wrote a short letter describing the moment he decided to get into the lifeboat. He admitted feeling torn, ashamed, unsure. But in the end, he did what most people would do if we’re being honest: he saved his own life.

He wrote, “I found myself looking for and waiting for any possible chance for survival… I saw a lifeboat being lowered with two vacant seats. A crewman shouted, ‘Room for two more!’ and a man jumped in. I decided I should wait no longer.”

That tiny decision, made in seconds, would shape the rest of his life.

Forgotten But Not Gone

Hosono kept a low profile for the rest of his years. He eventually got his job back and raised a family. But the stain of surviving never fully disappeared. For decades, his name was left out of official Titanic survivor lists in Japan.

It wasn’t until nearly a century later that the narrative began to shift. In the early 2000s, his descendants started speaking publicly about what had happened to him. The tone had changed. People no longer expected men to die to preserve honor codes from another era. Instead, many saw his choice as deeply human.

What Would You Do?

That’s the uncomfortable question buried in Hosono’s story. Would you have stayed behind? Would you really have let that last lifeboat go?

It’s easy to say you would. Easy to imagine yourself the brave soul who gives up a seat, who goes down with the ship like the band or the captain. But when you’re on the deck, staring into freezing black water, everything changes. Suddenly, survival becomes very personal.

Hosono wasn’t a hero. But he wasn’t a villain either. He was a man, caught in a moment that history magnified, judged, and misunderstood.

A Belated Redemption

In 1997, James Cameron’s film Titanic reignited interest in the disaster, and in Japan, people remembered Hosono again. But this time, with sympathy. His letter was displayed publicly. His great-grandson spoke to media outlets. And people began to understand that the shame placed on him had more to do with rigid cultural expectations than with actual wrongdoing.

He didn’t push anyone. He didn’t lie. He didn’t steal a seat. He just sat down when someone said there was space. And then he lived. That’s it. That’s the whole scandal.

In a time when we admire vulnerability and authenticity, his story feels strangely modern. We see ourselves in him. He was scared. He was torn. He acted.

More Than Just a Footnote

Masabumi Hosono reminds us that history isn’t just made by the heroes and the villains. It’s also made by the quiet ones. The people who lived through something and carried it silently. The ones judged by headlines and forgotten by history books.

He wasn’t the man who played the violin while the Titanic sank. He didn’t go down with the ship. But he left behind a story worth telling. Not because it’s dramatic, but because it’s deeply human.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s the kind of survival we need to hear more about.

Sources:

1. Business Insider – The tragic tale of Masabumi Hosono, the Japanese Titanic survivor who was ostracized for not going down with the ship

2. Encyclopedia Titanica – Masabumi Hosono

3. Deep English – Titanic Survivor Branded A Coward For Not Dying