Imagine holding a blade older than history, forged not in a blacksmith’s fire but in the heart of a dying star.

That actually happened. And it wasn’t science fiction. It was Inuit ingenuity.

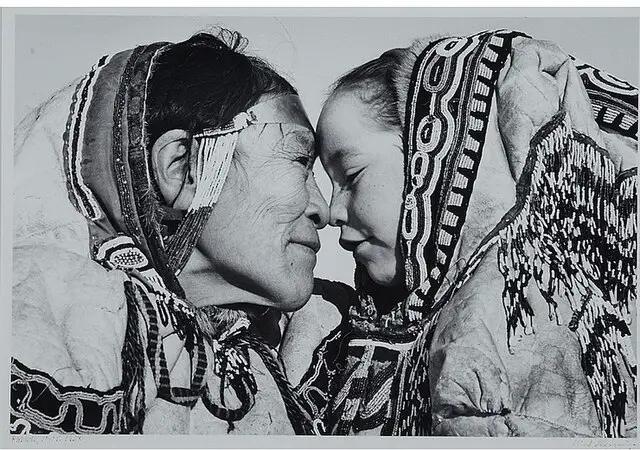

For centuries, long before steel ever touched the Arctic, the Inuit people of Greenland were using iron. Not imported, not traded. Mined from a fallen meteorite that had crash-landed into the icy earth thousands of years ago. That chunk of space rock would become the stuff of legend, science, and survival.

The Sky Falls Over Greenland

Roughly 10,000 years ago, a massive iron meteorite slammed into northwest Greenland. When it broke apart, it left behind three major fragments now known by the names: Ahnighito, the Woman, and the Dog. (Yes, really. More on that in a minute.)

To the Western world, this was just another geological oddity. To the Inuit? It was a godsend. Iron was impossibly rare in the Arctic, and this rock from the sky gave them something no one else in the region had: the power to make metal tools.

Turning Star Metal Into Survival Tools

So how do you turn a literal meteorite into a knife?

The Inuit didn’t have forges or smelting equipment. Instead, they used hammerstones to chip and flake pieces of meteoric iron, often combining it with bone or antler handles. The result was a cutting tool that could gut a seal, slice a hide, or carve a sled with cosmic efficiency.

That may not sound flashy, but remember: everyone else in the region was still using stone or bone. Meteoric iron gave the Inuit a serious technological edge. These weren’t just knives, they were instruments of survival in one of the harshest environments on Earth.

Names From the Stars

The three largest meteorite chunks were eventually named Ahnighito (the heaviest, at over 30 tons), the Woman, and the Dog. Those names come from Inuit oral tradition, where the fragments were seen almost as a family that had fallen from the heavens.

In the 1890s, famed Arctic explorer Robert Peary learned about these meteorites and, in true colonial fashion, arranged to have them shipped back to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. It took years, a specially constructed railroad, and a ton of muscle to get Ahnighito onto a boat.

Today, it still sits in that museum, resting on massive supports because it’s so heavy it would collapse the floor otherwise. Some Inuit people still feel the loss deeply, not just of an artifact, but of something sacred and practical, stolen in the name of science.

Cosmic Iron, Human Legacy

What’s wild is that this isn’t even unique to the Inuit. Around the world, other ancient cultures also used meteoric iron before learning how to smelt it from ore. King Tut’s dagger? Made from meteoric iron. Some of the earliest iron beads in Egypt? Same.

But the Inuit story stands apart because of how long they used it, well into the 19th century, and how they adapted without melting or forging. They worked with what they had. Literally chipped away at the sky until it became a tool.

Final Thought: A Knife That Fell From Heaven

Next time you see a shooting star, remember: to the Inuit, one of those became a knife. Not a legend. Not a trinket. A real, everyday tool that helped them survive, thrive, and shape their world.

It’s one of the most quietly astonishing stories in human history, not because of the iron, but because of the people who figured out how to use it. No blast furnace. No engineers. Just hands, stone, and sky.

Sometimes, the sharpest minds don’t need modern tools. Just a little bit of stardust.

Sources:

1. Smithsonian Magazine: The Iron from the Sky

2. AMNH: Cape York Meteorites

3. NASA on Meteoric Iron Use