Imagine creating 70 paintings in 70 days while your mind slowly unravels. That was Vincent van Gogh’s final chapter.

The Sky Was on Fire, and So Was He

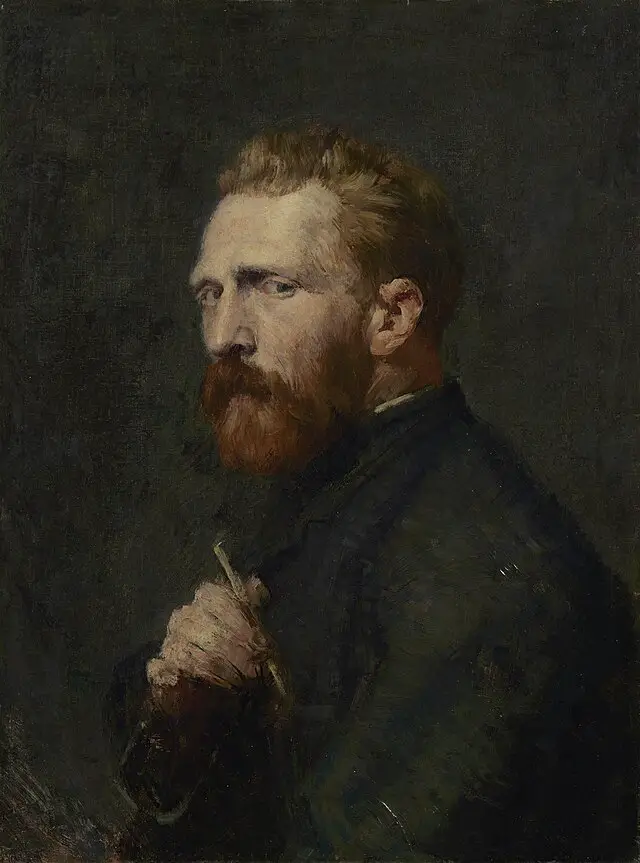

The summer of 1890 in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, was filled with light. Thick wheatfields shimmered under a yellow sky. The cypress trees stood like sentinels, and the wind had a voice. Into this quiet village arrived a man with a straw hat, red beard, and eyes that held the storm. Vincent van Gogh, 37 years old, broke, half-mad, and about to create the most feverish burst of work in the history of modern art.

This is where the clock starts ticking. Seventy days. Seventy paintings. Each one a grenade of color and emotion. Each one painted not with calm precision, but with a kind of defiant desperation.

Why Here? Why Now?

Van Gogh moved to Auvers after being released from the asylum at Saint-Rémy. His doctor, a man named Paul Gachet, was an art-loving physician who offered him care, company, and a room to rent. Gachet was eccentric, maybe even a bit unstable himself, but he was kind. Van Gogh trusted him.

He thought Auvers might be healing. A slower pace. No more institutions. More sky, more time, more freedom. But peace didn’t come. It never really had.

The Paintings Got Louder

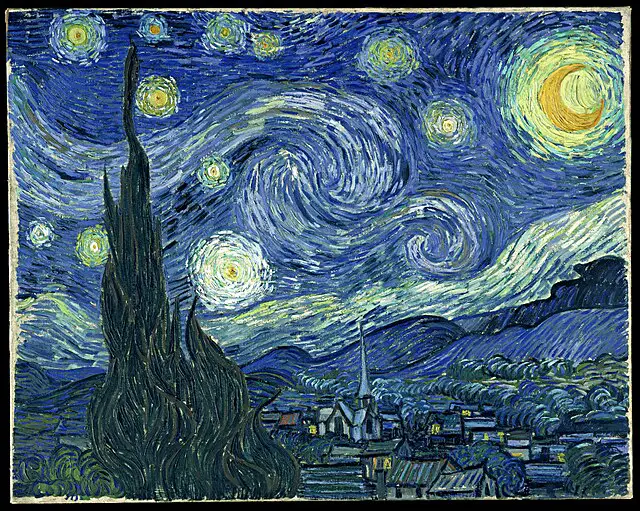

You can see it. The canvases from those final weeks are electric. They almost vibrate. “Wheatfield with Crows.” “Portrait of Dr. Gachet.” “Thatched Cottages at Cordeville.” “The Church at Auvers.”

Everything is alive and on edge. The brushwork slashes. The colors pulse. The perspectives tilt. These aren’t just landscapes. They’re emotional earthquakes. You get the feeling Van Gogh wasn’t trying to show you a field. He was trying to show you what it felt like to stand in that field with your heart racing and your head full of bees.

Letters From the Edge

Van Gogh wrote letters constantly, mostly to his brother Theo. They’re heartbreaking. He talks about exhaustion. About loneliness. About the fear that he would never truly recover. “I feel like a failure,” he wrote. And also, “The sadness will last forever.”

But he also talks about hope. About beauty. About the colors he still wanted to chase. It’s the mix that makes you ache. He wasn’t hopeless. Not completely. He was still fighting.

July 27, 1890

The official story is this: Van Gogh walked into a wheatfield and shot himself in the chest with a pistol. He didn’t die immediately. He staggered back to his room, wounded but conscious. When the doctor arrived, Vincent reportedly said, “I shot myself. I only hope I haven’t botched it.”

He died two days later. Theo was at his side.

There’s debate about what really happened. Some now believe it might have been an accident or even foul play. But most agree it was suicide. And even if it wasn’t, the pain that led him into that field was real.

The Aftershock

Theo died just six months later. He was buried next to Vincent. They had lived their adult lives tethered to one another, two sides of the same fragile coin. Without Vincent, Theo faded fast.

It was Theo’s widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, who gathered Vincent’s work, preserved his letters, and pushed for exhibitions. She understood what no one else seemed to: that Vincent had given the world something extraordinary.

From Madness to Immortality

Today, we call Van Gogh a genius. A pioneer. But during his life? He sold one painting. Just one. He was mocked, pitied, ignored.

But those final 70 days? They hold the proof of everything he was. The fury. The tenderness. The need to speak through color what words could never quite touch.

He didn’t paint for critics. He painted for survival. For dignity. For meaning. Maybe that’s why his work still moves people so deeply. It wasn’t meant to impress. It was meant to feel.

Why It Still Matters

Van Gogh reminds us that beauty can rise from agony. That even in the thick of despair, creation is possible. Even vital.

He painted right up until the end. In pain. Alone. But still painting. Still seeing. Still choosing to notice the curl of a leaf, the arc of a steeple, the color of a shadow.

Seventy days. Seventy paintings. A life burned bright and fast. But not forgotten.

So next time you see a swirling sky or a field that looks like it might lift off the canvas, remember: that came from a man who almost didn’t make it through July.

Sources:

2. Naifeh, Steven & Smith, Gregory White. Van Gogh: The Life (2011)